Category: Economics

-

Japan GDP growth first quarter 2017 – Gerhard Fasol interviewed by Rico Hizon on BBC TV

Japan’s economy grows five quarters in a row, and Japan Post books losses of YEN 400.33 billion (US$ 3.6 billion) for an acquisition in Australia by Gerhard Fasol Japan GDP growth first quarter 2017, growth of 2%/year. Still, Japan’s economy is the same size as in 2000, while countries like France, Germany, UK today are…

-

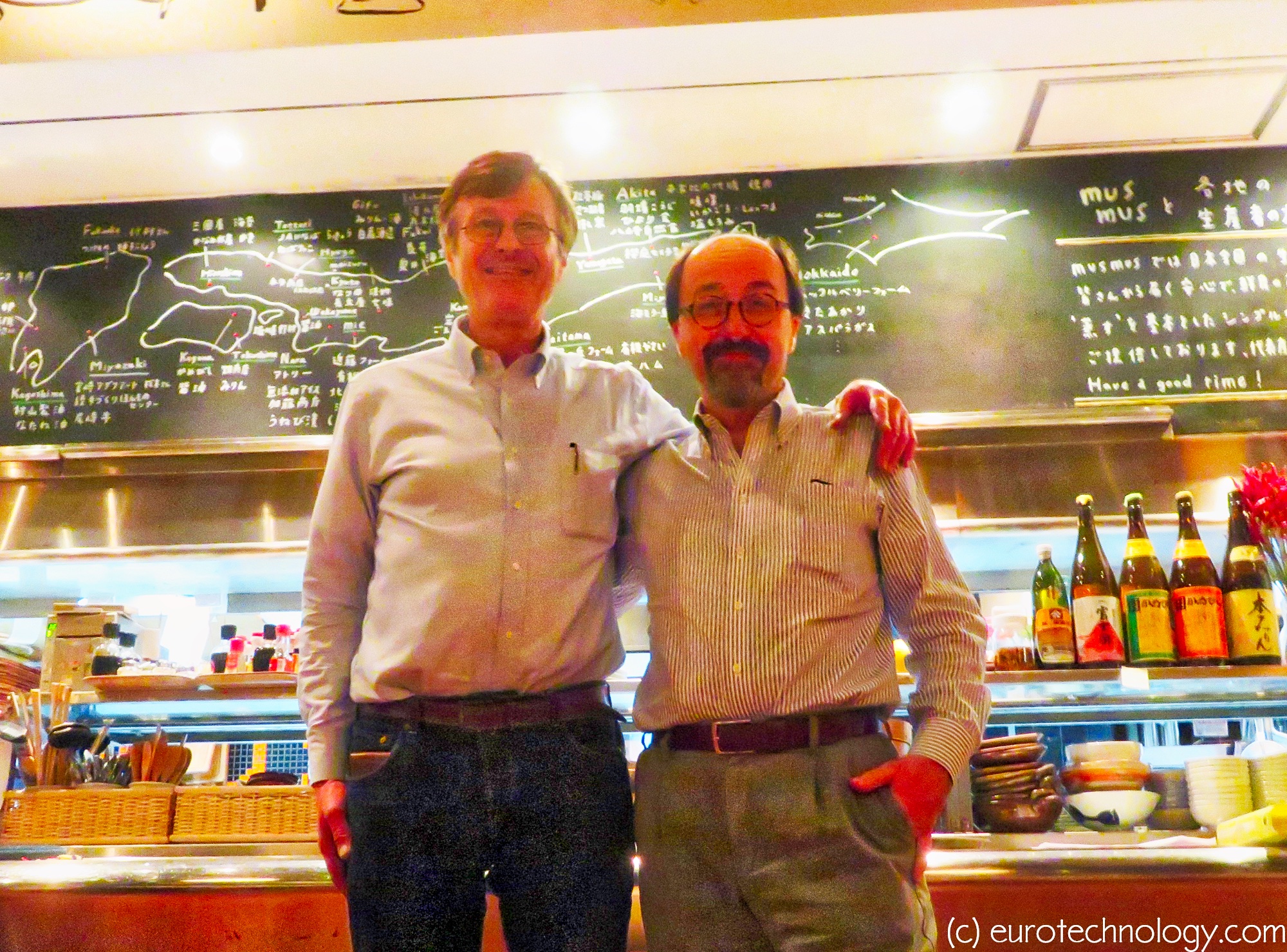

Women determine Japan’s future – Bill Emmott and Gerhard Fasol discuss Japan’s future

Bill Emmott and Gerhard Fasol about the future of Japan and the power of Japanese women Bill Emmott is an independent writer and consultant on international affairs, board director, and from 1993 until 2006 was editor of The Economist. http://www.billemmott.com Gerhard Fasol is physicist, board director, entrepreneur, M&A advisor in Tokyo. http://fasol.com/ women determine Japan’s…

-

Economic growth for Japan in 2016?

Japan’s companies are key to Japan’s growth by Gerhard Fasol Economic growth: Almost everyone agrees that economic growth is preferred over stagnation and decline. Fiscal policy and printing money unfortunately can’t deliver growth. Building fresh new successful companies, returning stagnating or failed established companies back to growth (see: “Speed is like fresh food” by JVC-Kenwood…

-

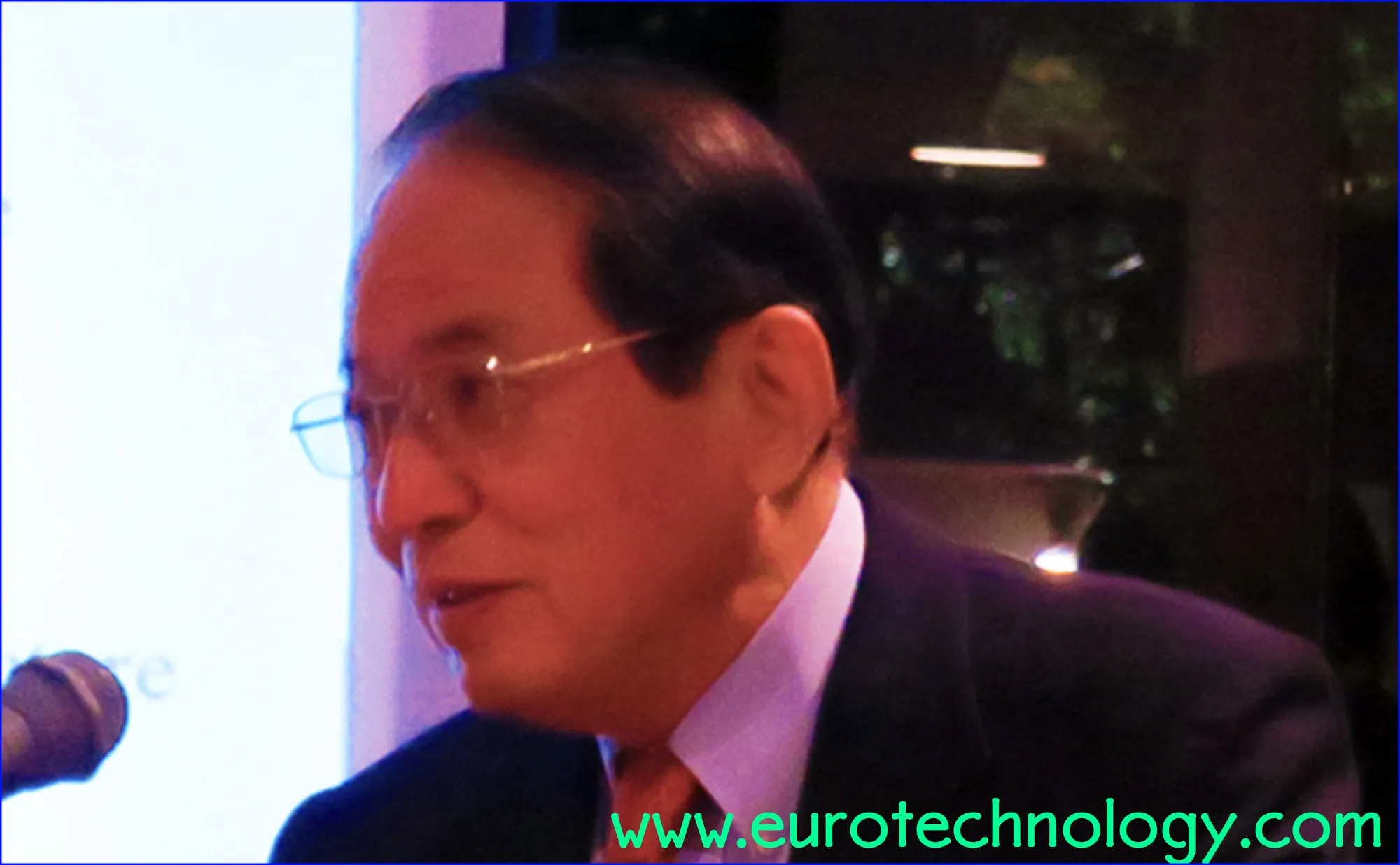

Japanese management – why is it not global? What should we do? asks Masamoto Yashiro

Masamoto Yashiro: Japan leader and Chairman emeritus of Esso, Exxon, Citibank, Shinsei Bank Masamoto Yashiro at brainstorming by President of Tokyo University Masamoto Yashiro’s talk notes by Gerhard Fasol and with permission and reviewed by Masamoto Yashiro Masamoto Yashiro is a legend in Japan’s banking and energy industry. He built Shinsei Bank from the ashes…

-

Japan new energy policy creates opportunities for renewables, smart grid and more – interview by The Economist

Japan energy policy: interview for The Economist on YouTube by Gerhard Fasol Japan energy policy – interview outline: Japan energy policy Question: Is the new energy policy of Japan’s Government an appropriate response to the situation or a missed opportunity Answer summary:The Government in its new strategy summarizes Japan’s energy situation and proposes a cocktail…

-

Abenomics – and – Why did Japan stop growing?

Professor Takeo Hoshi, Professor of Economics at Stanford, about Abenomics success probability Abenomics success probability is 12%, 88% probability of failure Takeo Hoshi, Professor at Stanford University, who devotes his life to work on Japan’s economy at US Universities, gave a talk at the Swedish Embassy organized by the Stockholm School of Economics on Monday,…

-

Japan Galapagos effect

Japan Galapagos effect: Dr. Gerhard Fasol dissects the history behind Japan’s unique international market separation By Hugh Ashton Originally posted by ACCJ Journal on January 15, 2011 in “Chamber Events”based on a talk given by Dr. Gerhard Fasol to the Members of the American Chamber of Commerce (ACCJ) on July 12, 2010, at the Westin…

-

Investor Club: What crisis? Meet some booming Japanese companies

It’s not all doom and gloom here in Japan. Nintendo’s sales and operating profits are rising 8.8% year-on-year. KDDI saw its net profits increasing 59% year on year. Yahoo Japan increases dividends by 22%-25% for 2008. Who are today’s winners in Japan’s IT industry? Gerhard Fasol will show us how and why some great Japanese…

-

High-tech market entry to Japan: new opportunities versus old mistakes (Stanford University lecture)

Success stories vs failure. Why some foreign companies succeed in Japan’s high tech sector, and why others fail. High-tech market entry to Japan: Stanford University Japan Technology Center lecture by Gerhard Fasol New opportunities vs old mistakes – foreign companies in Japan’s high-tech markets Stanford University lecture, given on October 28th, 1999 This lecture was…