Category: Leadership

-

Japan GDP growth first quarter 2017 – Gerhard Fasol interviewed by Rico Hizon on BBC TV

Japan’s economy grows five quarters in a row, and Japan Post books losses of YEN 400.33 billion (US$ 3.6 billion) for an acquisition in Australia by Gerhard Fasol Japan GDP growth first quarter 2017, growth of 2%/year. Still, Japan’s economy is the same size as in 2000, while countries like France, Germany, UK today are…

-

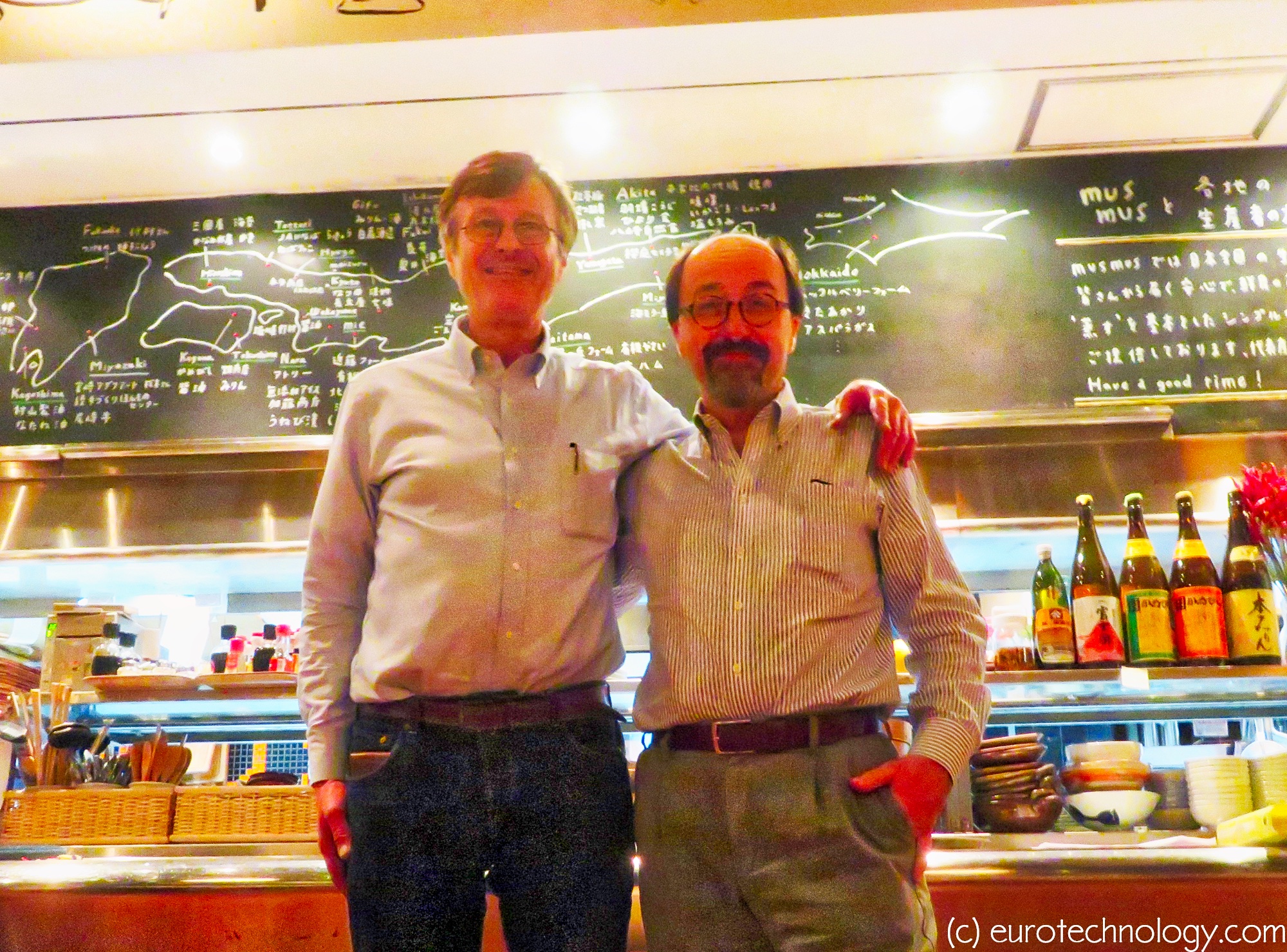

Women determine Japan’s future – Bill Emmott and Gerhard Fasol discuss Japan’s future

Bill Emmott and Gerhard Fasol about the future of Japan and the power of Japanese women Bill Emmott is an independent writer and consultant on international affairs, board director, and from 1993 until 2006 was editor of The Economist. http://www.billemmott.com Gerhard Fasol is physicist, board director, entrepreneur, M&A advisor in Tokyo. http://fasol.com/ women determine Japan’s…

-

Volkswagen Suzuki divorce – lessons for partnership strategies in Japan

“Mr Suzuki didn’t want to be a VW employee” (Prof. Dudenhoeffer via Bloomberg) Partnerships in Japan without meeting of minds, trust, and communication don’t work by Gerhard Fasol, All Rights Reserved. 18 September 2015 On 9 December 2009, Volkswagen-CEO Mr Martin Winterkorn and Suzuki-CEO Mr Osamu Suzuki at a press conference in Tokyo announced a…

-

Japanese management – why is it not global? What should we do? asks Masamoto Yashiro

Masamoto Yashiro: Japan leader and Chairman emeritus of Esso, Exxon, Citibank, Shinsei Bank Masamoto Yashiro at brainstorming by President of Tokyo University Masamoto Yashiro’s talk notes by Gerhard Fasol and with permission and reviewed by Masamoto Yashiro Masamoto Yashiro is a legend in Japan’s banking and energy industry. He built Shinsei Bank from the ashes…

-

Sir Stephen Gomersall on UK-Japan business and globalization

Sir Stephen Gomersall: former British Ambassador to Japan and Chairman of Hitachi Europe Sir Stephen Gomersall on UK-Japan business and globalization: Globalization and the art of tea Hitachi – Japan’s most iconic corporation – under the leadership of Chairman & CEO, Hiroaki Nakanishi embarked on the “Smart Transformation Project” to globalize, to face a world…

-

High-tech market entry to Japan: new opportunities versus old mistakes (Stanford University lecture)

Success stories vs failure. Why some foreign companies succeed in Japan’s high tech sector, and why others fail. High-tech market entry to Japan: Stanford University Japan Technology Center lecture by Gerhard Fasol New opportunities vs old mistakes – foreign companies in Japan’s high-tech markets Stanford University lecture, given on October 28th, 1999 This lecture was…