Tag: Japan’s future

-

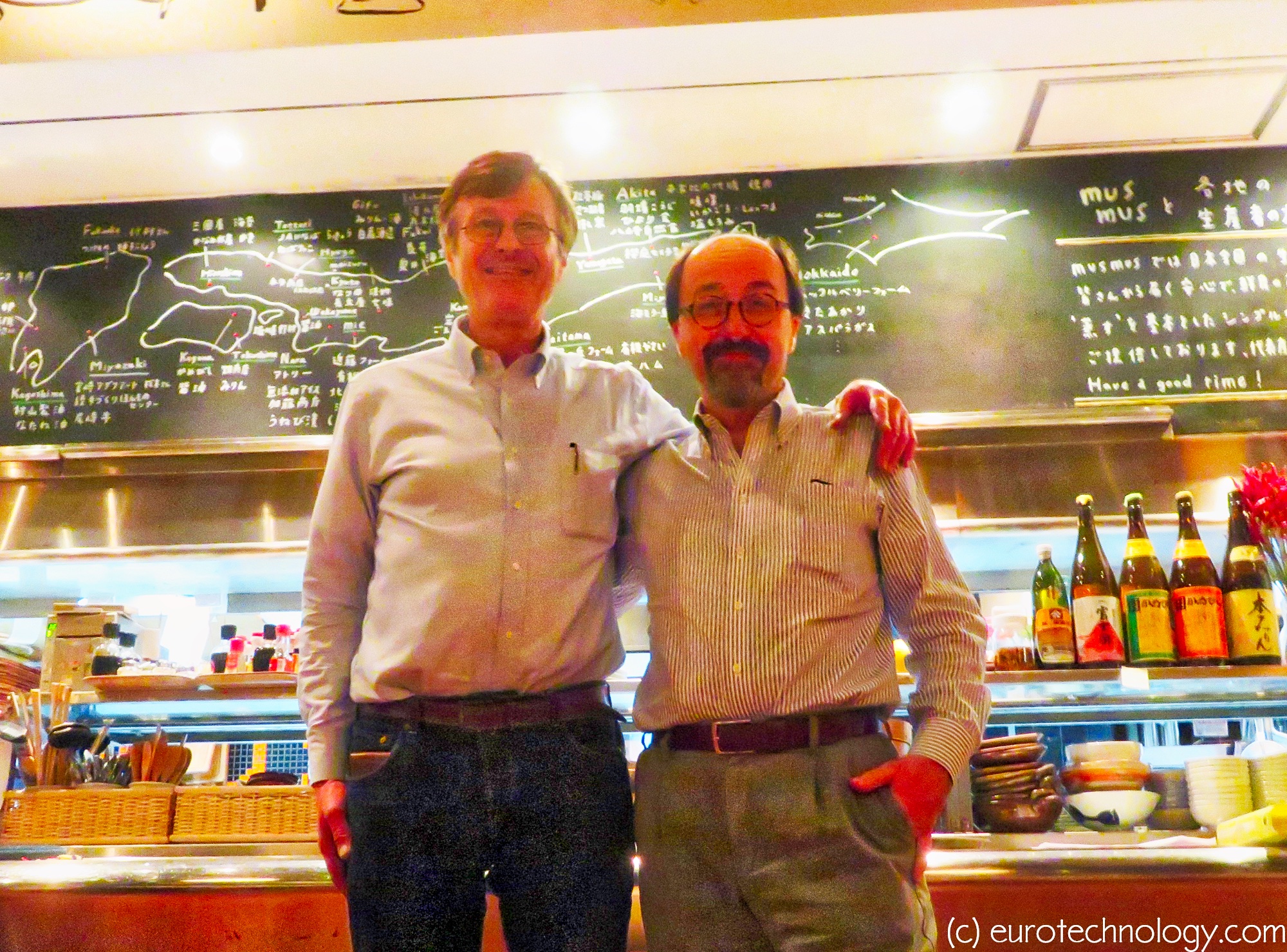

Women determine Japan’s future – Bill Emmott and Gerhard Fasol discuss Japan’s future

Bill Emmott and Gerhard Fasol about the future of Japan and the power of Japanese women Bill Emmott is an independent writer and consultant on international affairs, board director, and from 1993 until 2006 was editor of The Economist. http://www.billemmott.com Gerhard Fasol is physicist, board director, entrepreneur, M&A advisor in Tokyo. http://fasol.com/ women determine Japan’s…